Although this post is coming a little late, this is a reflection about our work in our MPX program for the second week of the school year. Not surprising, most teachers spend some of the initial time with their students setting the context for what they are doing. We take time to establish our norms, have students understand our routines and rhythms of the class so that we make it possible for them to work efficiently and to stay on task when they are with us. In our work with MPX, we did a few things that set the context for our work. It struck me that the quote that the title is based on (which is from Lewis Carroll) kept coming up as we were working with our students in these first few weeks on our mini project on conflict resolution in society. Let me give three examples of how this played out in our work this week.

Class Norms

We took time in our class to have the students consider what are the kinds of behaviors, attitudes and beliefs we bring in when we work as a class. We did a co-construction activity where the students offered ideas, and then we distilled those over 100 thoughts down to 19 key statements that they made about what it means to learn in our class. The key thing was to make sure the words were theirs, since our goal is to give them feedback and hold them to these agreed-upon expectations.

One of the beautiful things about having these posted clearly in the room is that we can proactively challenge and point out to the students that these are the things that powerful learners do. It acts as our roadmap to a class culture that will move us forward productively.

Assessment Criteria

When we ask students to produce quality work there are really a few ways for us to get there:

– looking at models that we admire and can use to help us set the language for what excellence looks like

– a process for feedback that allows learners to look at their current states and to know where they need to move next

– and lastly clear criteria that we have agreed on about what the end should look like.

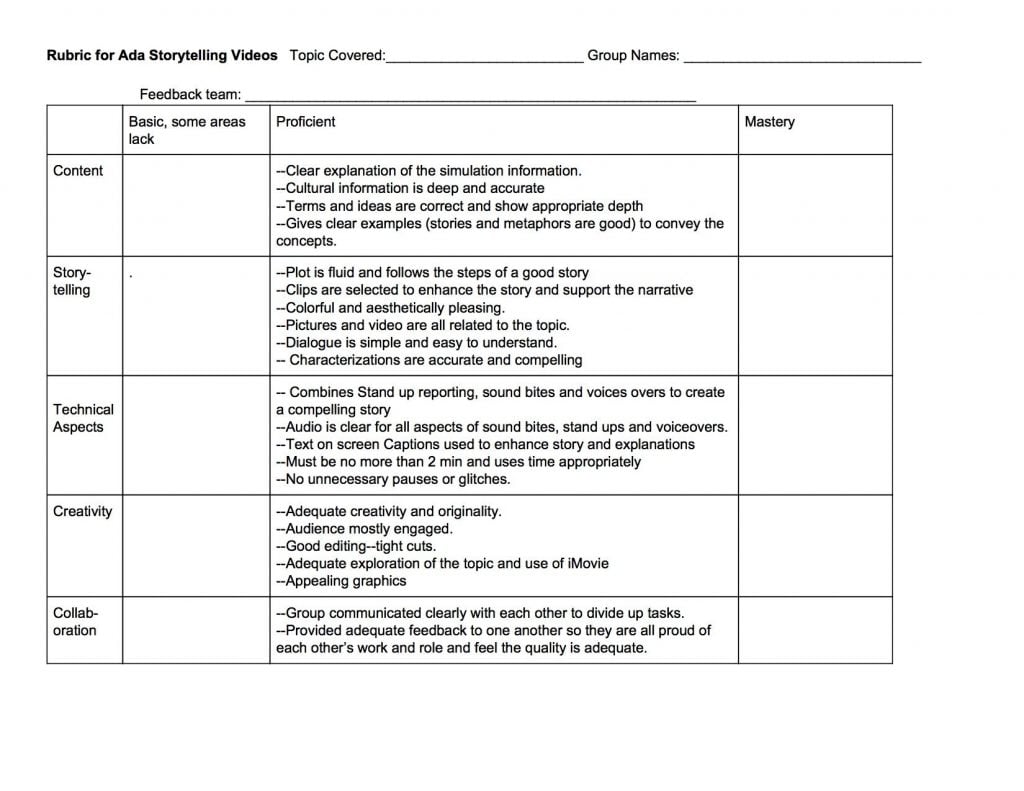

One of our artifacts from the society conflict activity was a two minute video that the students made in news story format that would tell a story of conflict and resolution in society. In order to help the students get there, we needed to know the language of good storytelling, and then we needed a tool to help us operationalize our ways to look at our work and to judge whether it was of high enough quality. The rubric we used for this project is here:

The language from this came from our own research, from looking at quality examples, and by using expertise to help us make decisions about what goes into good storytelling. The students used this rubric to give each other feedback multiple times, and it was used in the final assessment as well.

Project Sheets and Descriptions

At the start of any project, we give the students a map out of what that project will unfold like with clearly defined goals, an essential question, an outcome that is important and challenging and the steps that are required to get there laid out with enough detail that they know what needs to happen to get from the start to the finish. When we do our professional work with teachers around the state, this is the key thing that we tried to instill in those teachers – that without a roadmap and clarity around the means by which students will have time to understand, give feedback and reflect on their learning, the likelihood of getting to the end is drastically less. We have seen many teachers talk about how they have implemented projects, and only a few or some of the students “got it” and produce a product that they had hoped for. More often than not, it is not a fault of the students, but lack of clarity of the roadmap on how to help them get there.

As we continue to move on into the school year we hope to continue to provide clear guidance for our students so that they do the traveling, but they have the support they need to end up in the right destination. It’s