The week of December 7, Kaile and I attended the national Learning Forward Conference in Boston, Massachusetts. While the weather was a reminder that we were far from Hawaiʻi, the conversations were anything but cold. Across three days, a set of powerful through-lines emerged—about leadership, systems, voice, and what it really means to keep learning centered on students in uncertain times.

The conference opened Monday morning with a keynote from Cornelius Minor, Keeping the Focus on Kids in Uncertain Times. Minor grounded the week in a moral imperative: when systems feel stressed or unstable, the temptation is to retreat into control and compliance, but our responsibility is to double down on relationships, humanity, and care. His message was a steady reminder that equity work begins with how we see children—and whether our decisions consistently reflect that focus.

That idea of systems shaping experience carried directly into our Monday morning session with our friends at the High Tech High Graduate School of Education team, Process Mapping Your Way to Better Systems, which drew on work from the National Coalition for Improving Education. Rather than treating dysfunction as a people problem, the session invited us to look closely at processes—how work actually moves through a system, where friction shows up, and how well-intentioned structures can quietly undermine learning. It reinforced a recurring theme of the week: experience is the system. During the session, I spent time reflecting more deeply on our process for coaching calls with teams of teachers. Time well spent!

Monday afternoon’s workshop, “Core, Contingency, and Paradox: Leading Systems for Continuous Improvement,” by Jal Mehta reframed school improvement as human, not technical, work. Drawing on complexity science and Margaret Wheatley’s Six Circle Model, he emphasized that sustainable change requires attention both above and below the “green line.” Structure, process, and strategy matter, but relationships, identity, trust, and shared meaning are what allow improvement to take root. Mehta challenged leaders to match approaches to the type of problem they face and to live within productive tensions—action and reflection, order and emergence. Improvement, he argued, is less about control and more about learning our way forward.

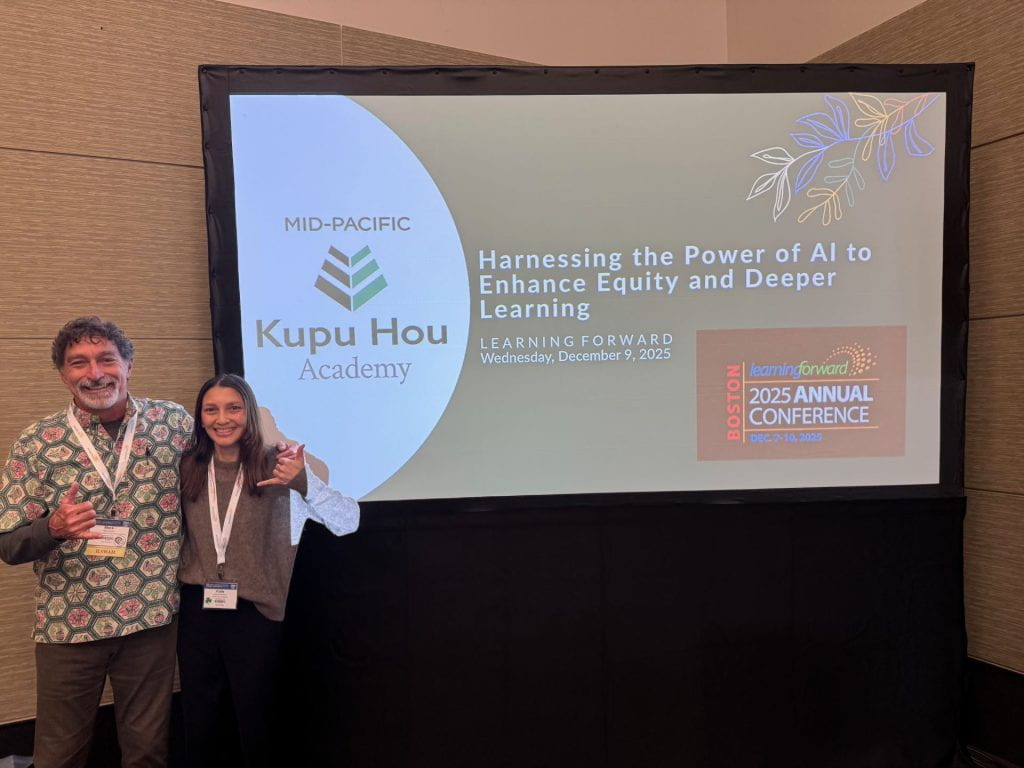

Tuesday morning began with the keynote Pedagogy of Voice: Street Data and the Path to Student Agency from Shane Safir and Sawsan Jaber. Their work reframed data as something gathered through listening rather than extracted through dashboards. Student voice, they argued, is not feedback—it is access to power, belonging, and authorship. Crucially, they emphasized symmetry: if we want agency for students, adults must experience it as well. That notion of symmetry carried into Tuesday morning’s session, Leading for Deeper Learning, led by Melissa Daniels and Stacy Lopez from High Tech High GSE. They challenged leaders to examine whether adult learning truly mirrors the inquiry, collaboration, and reflection we value for students. School culture, they reminded us, is shaped less by vision statements and more by the daily experiences people are invited into. Tuesday afternoon brought us closer to home with Transform Your School Through Collective Action, led by Joe Passino, principal of Princess Keʻelikōlani Middle School in Honolulu, and Bette Moreno. We were proud to hear how their leadership moves—high expectations paired with high support, visible collaboration, and shared responsibility—are shaping student commitment and learning. Their work made clear that transformation is not driven by heroics, but by culture built collectively over time. Wednesday morning, we closed our conference experience by facilitating our own session on AI for Equity and Deeper Learning. Rather than positioning AI as the work itself, we framed it as a mirror—one that reveals values, assumptions, and design choices. The thoughtful engagement of participants suggested the field is ready to approach AI with discipline and purpose, not hype.

Wednesday morning, we closed our conference experience by facilitating our own session on AI for Equity and Deeper Learning. Rather than positioning AI as the work itself, we framed it as a mirror—one that reveals values, assumptions, and design choices. The thoughtful engagement of participants suggested the field is ready to approach AI with discipline and purpose, not hype.

I left Boston encouraged. Across sessions, the message was consistent: deeper learning emerges when we align systems, culture, and leadership around humanity, voice, and agency—for students and adults alike.