Deeper Learning 2014 Reflection

I suppose I should start my reflection by reminding myself what the purpose of the conference was based on their own language:

Connect – I have made several new connections and have deepened my relationship with several old connections.

Innovate – I have new ideas for how to better support deeper learning in my organization, school, or classroom.

Experience – I will experience deeper learning for myself, which will help me to apply deeper learning principles to my own work.

so measured against their own questions, here is some of my thoughts

***It is worth pointing out that ALL the conference materials for the sessions are free and available at : https://sites.google.com/a/hightechhigh.org/dl2014-workshops/ **********

Wednesday: Deep Dive: Teaching Science with Robots with Dr Karl Wendt

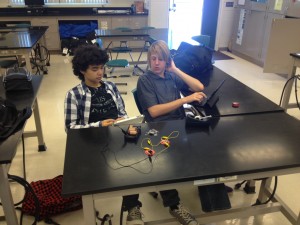

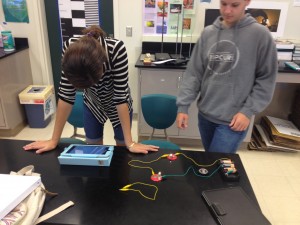

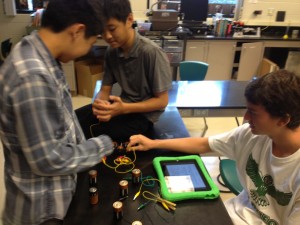

After walking us through a series of robots that he had built – from underwater robots to programmable motorized robots – Karl introduced us to the project of the day – building, and testing a small entry-level robot that cost less than $10 to build called spout.

resources for all of his work are located here:

https://sites.google.com/site/discovercreateadvance/home

One of the strengths of what he’s doing, is he made a series of short instructional videos that show how to build the robot. My partner was Ben Daley, and we agreed that by doing it as a series of self directed videos, there was a sense of pacing and authenticity in constructing that would’ve been very different if it’d been synchronously teacher led. We found his work on these videos to be excellent, and felt that we could initiate this project right away.

My Take Aways: The thing that struck me about this project/deep dive was that there was a good principle at play here: the fun part begins with the students building the robot. The hook is that in order for the students to solve the challenges, there needs to be enough core content knowledge (electricity, torque, light, friction, switches, etc.). Depending upon the way the activities of the challenges are set up, it’s entirely possible to cover different branches of physics and physical science. That to me was the strength of this activity – in the kind of work that we do with STEM education, the way to get kids engaged in by bringing some authentic design challenge or construction. Careful selection conversation and building an adequate resource library to support learning will help shape the learning that needs to be part of the academic rigor. Karl’s webpage for his resources is located here:

https://sites.google.com/site/discovercreateadvance/projects-1

Nice. Design.

After dinner, there was movie night and a panel discussion. The teaching channel has built a resource area that includes 50 videos that are meant to be short explorations of specific practices of schools in the network (looking at student work, advisories, comity partners, etc). this is a great source that I plan to use extensively in my work both on campus and outside of campus. the video series is located here:

https://www.teachingchannel.org/deeper-learning-video-series

Thursday:

Keynote with Ron Berger.

At some point, they will put the video of this keynote online. My guess it will be linked somewhere from the main page here: http://deeper-learning.org/dl2014/

Ron talked a bit about beautiful work, but the highlight of his presentation was four 8th grade students from Polaris Charter Academy in inner city Chicago. Their presentation was engaging, compelling, executed flawlessly, and a powerful story. Their work started with the investigation of the preamble of the Constitution but evolved into a study of gun violence in their neighborhood and what that told them about their freedoms and liberties and protection for the common good.

If this video does get put online, I highly recommend you watch it!

Looking at student work

attendees were put into groups of about 10 and given a piece student work. Facilitation of the session was led by a high-tech high student – our young lady was Killian and she did an excellent job leading and guiding our conversation. We looked at a compiled magazine that was created by sixth grade students to answer their big question of inquiry about different cultural and scientific theories about the end of the world. Our group had an excellent conversation about the things we saw that indicated deeper learning was evident, and places where we think the work could have been made stronger.

My take away from this one was a recognition that we need to more regularly look at our own student work as a team to help us decide how we are doing in looking at the rigor of our work, as well as how well it meets the other deeper learning characteristics like collaboration, developing academic mindsets, and problem solving.

Hour. Well. Spent.

Session 1: From Scratch with Scratch with Don Mackay

In this session, we were led through a series of design, Inquiry, and challenges about our understandings of electricity and magnetism. The documents for the workshop were here:

https://sites.google.com/a/hightechhigh.org/dl2014-workshops/workshops/session-1

After investigating , we were challenged with building a spinning motor from the equipment that he gave us. One of the things that made this interesting was the play between designing and exploring what we understood about electromagnetism. You can see that in the document linked above.

What were my big takeaways? I really feel that the pedagogical approach Don took was excellent – in our modeling terms from ASU, he began his studies with a discrepant event which challenged our notion of what we understood about the phenomena that underlie a particular field of study – in this case of electromagnetism. I like the bite-size nature of what he designed to explore this naïve understanding that we might have. I think this would suit well as ways to build knowledge in projects we do that a more extensive so that we’re creating place for rigorous conversation about what we understand. I’m going to try that with our light project will be doing in May.

Session 2: From Maker Space to Maker Campus with David Stephen

Wow. I had never met David until this day, but he was a teacher and the architectural designer of the interior spaces for the high-tech high buildings. Wow. He led an excellent, progressive session about the work that he does, and how he sees the importance of space as one of the ways to create and support student agency and 21st century teaching. Instead of summarizing what he did, here are my tweets I sent out for his session (there are in reverse order last to first):

#deeperlearning Session with David Stephen http://www.newvistadesign.net Provocative, Progressive, Powerful ideas on Agency by Design

#deeperlearning ideas for transforming spaces on the cheap: Make Space http://dschool.stanford.edu/makespace/ Great book. Easy to read. Low hanging fruit.

another great site on maker ideas – The Fab Lab http://fab.cba.mit.edu #deeperlearning

#deeperlearning the resource at @AgencybyDesign is tied to the Making Thinking Visible team as well. too cool!

Two useful resources on design: http://www.archachieve.net and http://www.designshare.com Great ideas abound! #deeperlearning

#deeperlearning SO much of our conversation on Agency by Design is reminding me of the work by Pine and Gilmore on the “Experience Economy”

#deeperlearning Agency By Design is a project out of Harvard Project Zero http://www.pz.gse.harvard.edu/agency_by_design.php …

#deeperlearning great turn of phrase from Davis Stephen: “airport grade” soft furniture. Love it! I’ve seen blown apart bean bag chairs!

#deeperlearning how to create inviting educational spaces – David Stephen uses the term ‘artifactorium’ to define exhibit space feel of HTH

#deeperlearning with David Stephen of New Vista Design talking about creating Student Agency By Design “From Maker Space to Maker Campus”

His three shared documents are on the materials page under session 2 :

https://sites.google.com/a/hightechhigh.org/dl2014-workshops/workshops/session-2

My Take Aways: This session rekindled in the and interest and passion around the importance of facility design editing needs to both support and lead teachers needs and behaviors into the place they need to be and to not reinforce things that are keeping them from advancing their professional practice. This topic has been of high interest to me since we started designing the Weinberg technology Plaza on our campus back in 1998. I definitely want to spend more time going through his resources and the agency by design website mentioned above.

Friday:

Session 3: Beautiful, Beautiful Math with Marcia Dejesus-Rueff

We had about 16 people in this session and we looked at ways to bring Art (poetry, dance, musics) into the mathematics that we do. I really liked the fact that her compelling case was mathematics is a search for patterns. These patterns can be found in poetry, dance, music, just about any art form we looked at a Dylan Thomas poem, and a Frank Lloyd Wright stained glass window as ways to create a linking between art and mathematics. Her documents can be found on the session 3 resources page here:

https://sites.google.com/a/hightechhigh.org/dl2014-workshops/workshops/session-3

my takeaways: I am still professionally challenged by looking for rigorously appropriate and engaging art that can lead to deep understanding of algebra to mathematical principles. the session provided me with opportunities to look at some other examples of how that looks.

Unconference Sessions:

Polls were taken on Thursday to determine the topics that would be offered on Friday. They were a variety of sessions offered that looked at everything from how to start your own deeper learning school, to what assessment looks like, to professional development strategies for teachers.

I attended:

The Leader’s Guide to Deeper Learning with Ken Kay and James Gibson

Ken is now at EdLeader21, and the session focused on walking us through the deliberate planning process and leading a school through transformation to deeper learning. At our tables, we modeled the process of developing core competencies, identifying new student skills necessary, and finished by proposing strategies to move towards these goals. The pictures of the chart paper are located here:

https://flic.kr/ps/2Rxk1U

the resources that they shared in the workshop are located in session 3 folder here:

https://sites.google.com/a/hightechhigh.org/dl2014-workshops/workshops/session-3

Other Thoughts:

Larry Rosenstock mentioned in his address the importance of recess for our group as a means to connect with familiar and new colleagues. I can’t agree more with that impact – whether it was lunch time, or just corridor conversations, or the after hour social events, the group used the time outside of the sessions at least as powerfully if not more so as a means to explore, connect, challenge and extend their thinking about their work. Looking towards our conference in November (http://sotfconf.org) there was a lot we could take away from what work here at deeper learning 2014.

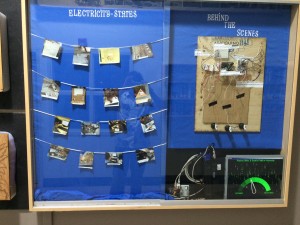

Student work is everywhere in High Tech High. Every time I come I take pictures to add to my collection – but this time with different intent for me. Since our students are going to work on building projects for the rest of the year, I wanted to capture some examples of already displayed student work to challenge my students to think of how they could make something as good as or better than what they see in the images. I have included a few examples below.

Last Word

One of the last things we were asked to do was fill out a post card with at least one idea we would implement. I wrote three:

for my MPX program, bring more student work protocols into our meetings

for our work with Kupu Hou, find ways to sustain a community of learner model that will more directly influence the attendees to stay connected over a longer period of time

for work with the Hawaii education leadership Summit, rethink what the topic might be by spending more time asking our intended audience what would suit their needs past so that we can align our work with their needs