This week’s post is framed around some experiences from this week, and some ruminations from weeks past. The title comes from a Winston Churchill quote that I have kept with me over last seven years or so from being involved in a new building design. And in light of the visits we had, some of the readings, and most importantly my own thoughts and experience, I have some thinking going on about design for formal and informal environments.

A week ago, we visited the Bishop Museum, and toured the newly reopened Hawaii Hall, as well as the science Center. Here were two facilities that had different origins — Hawaii Hall was built 100 years ago, and although it was face lifted in minor ways a few times, it was closed, reinvigorated, and reopened with a focus towards applying good visitor design ideas for the first time since it opened. Info here: The Science Center, on the other hand, was designed from the ground up and therefore had a different approach, look and feel, and goal.

On Tuesday, we visited the Waikiki Aquarium, and looked at its designs from the visitor experience, including the audio tour. The aquarium, has gone through a series of redesigns, and applying new exhibits and approaches over the years.

So along with that, I’ve been thinking about classroom design and library design in particular. My wife recently was at the Sinclair Library at the University of Hawaii and commented on the redesign which created a more friendly, open space for students. An area for socializing with food, coffee available for students, different configuration spaces with more openness, location of a Student Success Center to support studying, research, and other areas of student life. Essentially, they became more of a learning center, and less of an archive of paper text. As a result of small budgets, they did a lot of the work themselves: painting, receiving donations for furniture, rethinking spaces and making the most of what’s available. The results, a threefold increase in traffic over the last three months.

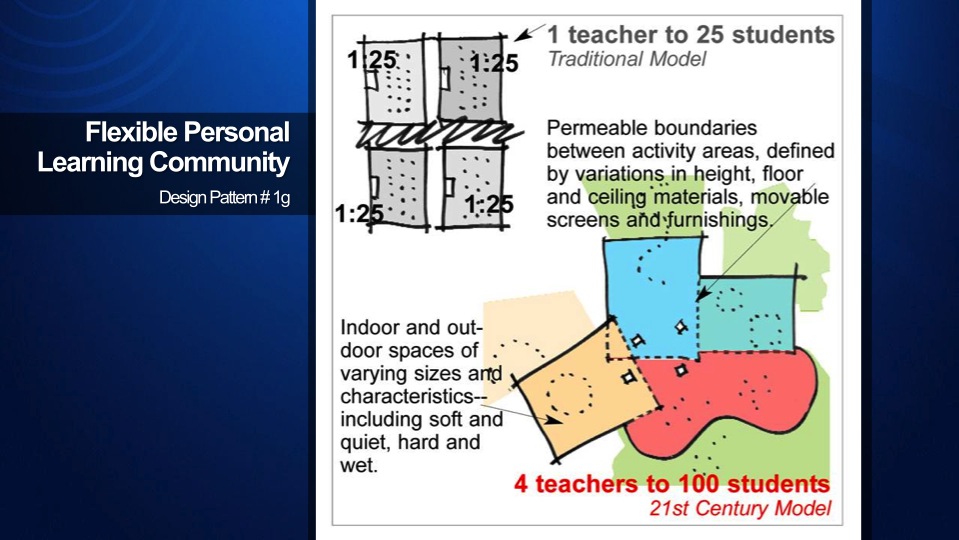

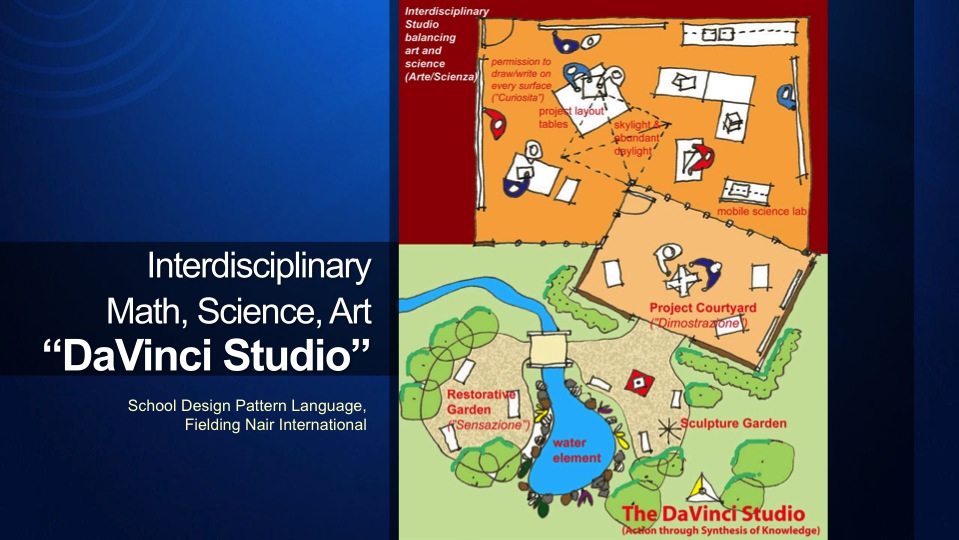

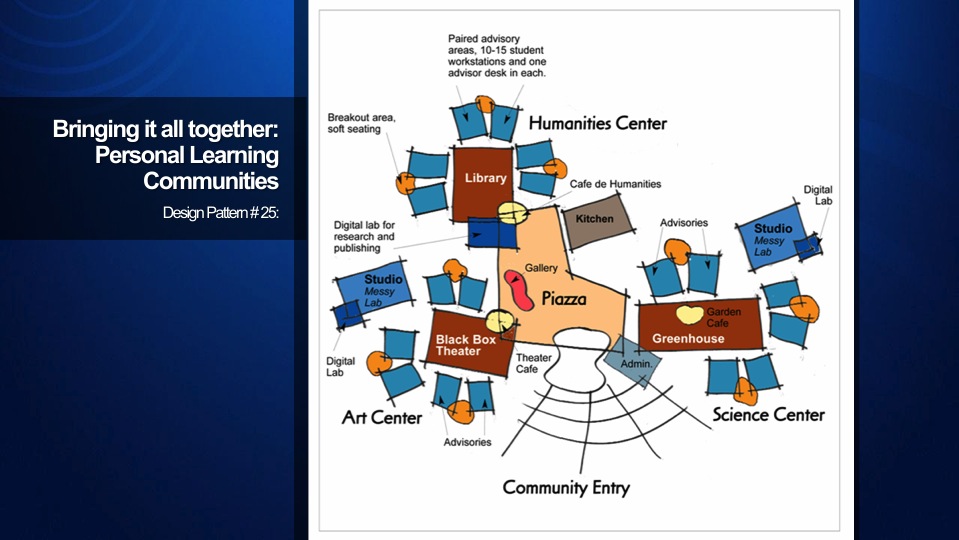

This made me think of a talk I heard in December 2008 by the architectural firm Fielding Nair International and their architect Randy Fielding titled “Transformation through Innovative School Design”. In this talk, he both talked about creating spaces for the 21st century, as well as gave design examples from his company and others. It made me think a bit about how a space like a library, or the Bishop Museum, or the Waikiki aquarium, would start if a donor gave them $2 million to redesign their facility. Make old things new? Or go back to square one, and design with a new eye?

To that end, Fielding discussed 20 modalities and four supporting areas that come into design ideas based on the social nature of humans and the way people learn. The modalities are:

independent study

peer tutoring

team collaboration

1 to 1 learning with teacher

lecture with teacher at Center stage

Project-based learning

technology-based with mobile computers

distance learning

research video wireless Internet

student presentations

performance-based learning

seminar style instruction

community service learning

naturalistic learning

social/emotional learning

art-based learning

storytelling (floor seating)

learning by building

team teaching

play-based learning

Not all of these modalities fit our thinking about informal learning spaces, at least in the way we think of them in exhibits in museums, but there are kernels in each one that support the readings that we have had two this semester.

More importantly, Fielding lays out four design areas that he thinks are significant in any new designs of formal (and informal, in my opinion) learning designs. They are (my explanations, not Randy’s):

The Campfire: a place where a group can gather around, share information, tell stories, and create a social context for their learning. This area has a sequence or synchronized mission to it.

The Watering hole: a more informal place to gather, that allows Asynchronous and unstructured sharing.

The Cave space: this area is designed for more quiet, reflective, individualized learning. A study area, a workroom, an out-of-the-way place.

Real life: spaces that are outdoors, or authentic for learning, experiment, grappling, learning with real objects.

At the end of his presentation, Randy shared a matrix that has been developed to aid schools in determining whether their design meets 21st-century goals. The instrument is called the Educational Facilities Effectiveness Instrument. The website where it is located is here:

The instrument includes criteria like entryway, technology readiness, supporting small learning communities, inclusion of learning studios, storage, transparency, casual eating areas, music and performance areas, outdoor learning, etc. In total there are 200 criteria that are assessed with this instrument. It includes images/exemplars of each category to prompt designers to consider ways to include these.

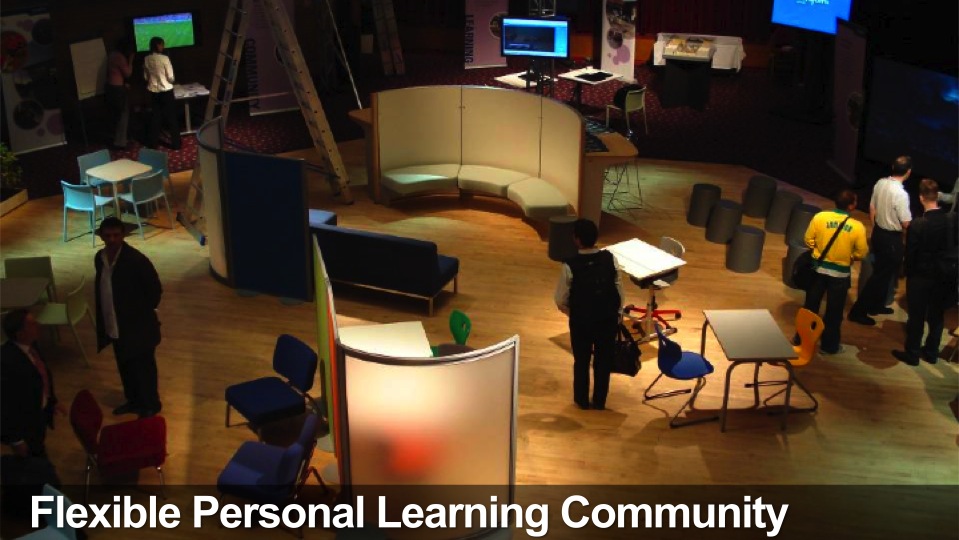

Some images from his slideshow might paint this a little better:

Are all of these criteria relevant for our thinking about informal learning environments? Probably not, but these prompts would lead one to really identify what areas in your informal environment you really wanted to focus on. For instance, maybe the addition of considering how outdoor areas might expand the kinds of experiences you offer is worth considering. The small way, the Sinclair Library transformation, models this. There was an outdoor lanai area that was redone, with furniture, better lighting, etc. and the result was increased usage on the part of students, who found the area inviting and welcoming. The Waikiki aquarium utilizes very well outdoor areas for their reef tank, small presentation areas, and fish and monk seal exhibit. The ability to be outside changes the feel of the environment, and creates context from the indoor and outdoor experiences of the facility.

So we have a wide range of opportunity as designers. Sometimes it’s weekend repainting and asking for donations of furniture like the Sinclair Library. Sometimes we have the opportunity to design from the ground up, as in the Bishop Museum and science Center. And other times, we can redesign with some resources on spaces into new learning areas. Instruments like the EFEI give a context upon which we can draw out our thinking and our understanding of the research on visitor experience and learning to best design old places new.